Wisdom, Knowledge, Faith, and Love: Waiting at the end of Kachemak Bay

By Hannah Rose Bradley, Anthropology PhD candidate, Princeton University

November 1958 “Every 40,000 years there is a downfall and we are now entering into the 6th downfall. Downfall means a natural condition which brings about a revitalizing of man … All buildings will be lowered to the earth and there will be no security in the hills, for they will also fall. Those who will be saved will only be those on the open planes, for they can move from their home. Those who will be able to stand are the individuals of the 144,000 elect”[1]

In 1956, prophet and messiah Krishna Venta took a group of his followers on an epic road trip from the Santa Susana Mountains in Northern LA up through Canada into Alaska, looking for the site for a second Wisdom Knowledge Faith and Love Fountain of the World. The End was coming: the race war and nuclear World War III foretold by Venta were expected for 1965 and 1975 respectively. According to Venta they would receive training from Master Krishna for 40 years while the Beast reigned, then they would go forth to “do battle”, “Their only armor will be the Love of God; their only weapons, the Truth of God”[2]. In Homer, Krishna Venta determined that a homestead at the head of Kachemak Bay was the right place for a second Fountain.

WKFL was not exactly a drop-out hippie commune of the 60’s and 70’s[3] but a slightly earlier generation of mystic communalism. Krishna Venta began lecturing in 1947, and founded the Fountain of the World in Box Canyon in LA. Krishna Venta proclaimed he had answers to life’s questions which could re-moor those lost in post-war America, and he provided a lifestyle to match, organizing both the inner and outer worlds of his followers around meditation—daily “Concentration”—study, and good works.

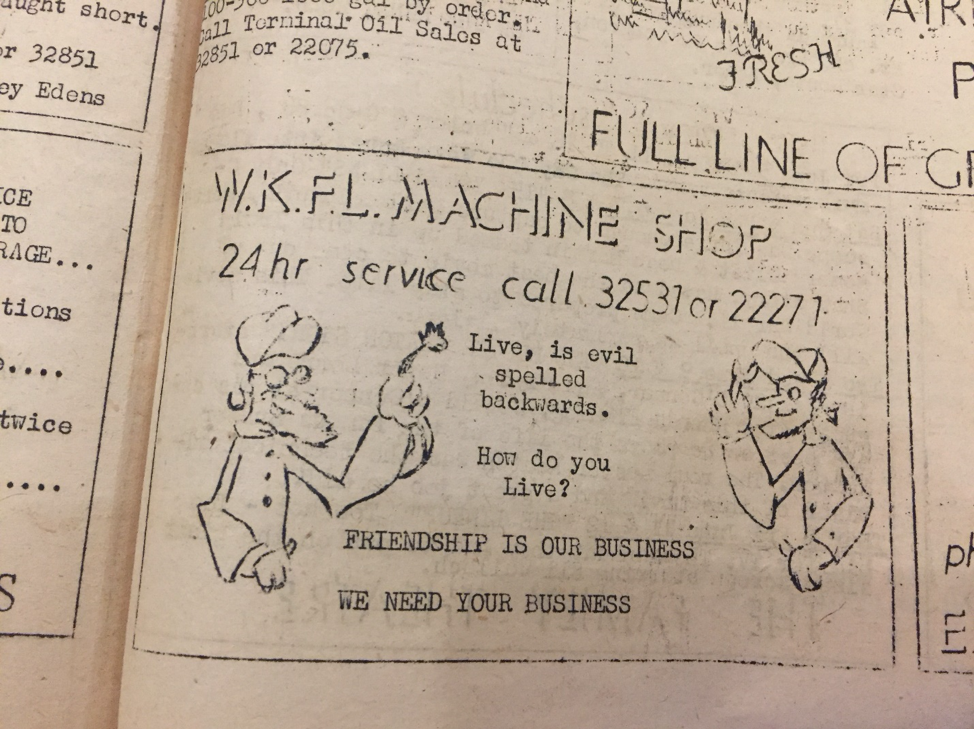

The “Barefooters” lived apart on their mountain campus and remote Alaskan village, but not totally isolated from the rest of society. In LA, they were known for their volunteer work with alcoholics and homeless, for fighting wildfires in their robes, and for coming to the aid of earthquake victims and a plane crash… In Homer, the Fountaineers owned a mechanic shop which provided some cash flow for the community, with witty ads in the Homer News. Their kids went to high school in town. In the winter, they sometimes even wore boots. And yet, they were the Elect, developing themselves to survive the coming wars.

© Pratt Museum Historical Archives

The ideal of the Alaskan wilderness obviously provided a contrasting “outside” and “beyond” the doomed teleology of the modern world. Indeed, the material reality of this landscape enveloped the little village of Venta in its strong sweeping cycles: the seasons, the tides, the shifting light. Nearby Homer is known as the “End of the Road”, and the Venta site is past even the end of paved and dirt roads, down a beach and across fast-flowing Fox Creek, across several miles of mudflats, in a canyon mouth at the furthest crook of Kachemak Bay where the Fox and Sheep Rivers drain from the Kenai Mountains. It seems the right place to hope to be past most details of civilization, though they didn’t expect to be alone there for some time.

Kachemak Bay would be a good place to wait to sense worldwide change. The Bay is a complex estuary, with five glaciers draining into it, and the second-largest tidal difference in the world. Twice daily, the tide drains and floods the bay, rising and falling up to 31 feet, mixing and aerating the nutritious swill of salt and fresh waters. It is a Critical Habitat Area and contains parts of the National Maritime Wildlife Refuge. Homer is the edge of the temperate rainforest, marking the boundary between cedars and taiga, between white and sitka spruce. A place on the edge of freeze, the edge of ecotone, always the edge of change.

But the Fountaineers are not here to believe or not in the Anthropocene. The world they built around the personality of Krishna Venta ended abruptly, in fire, in December 1958. Two disgruntled ex-members of the cult walked into a common building in the Fountain in Box Canyon in Los Angeles, to confront Krishna Venta, and detonated a home-made bomb that killed ten people, including themselves and Venta. He did not rise again, he did not return, and the community fizzled slowly without his charismatic leadership. Remnants of the community kept up the Alaska Fountain for several years, but it soon was abandoned.

Venta the place, this alder-screened corner of Kachemak Bay, remains their place of expectation. Here they were to wait for the race war, wait for the dawning of the New Age. Whether or not Krishna Venta was a sincere messiah, the community enacted devotion to their lifestyle and direction, right in this wide clearing, rimmed below with tall angular cottonwoods.

I last visited Venta at peak November high tides, the second highest high of the year, just a few tenths of a foot less than December’s. We came from another homestead, further up the river, to the edge of the Flats to see the Big Tides fill meadow edges, into the brim of the treeline, to see how far the waters might creep with the right encouraging wind. Then we picked our way over the frozen swamp to look onto the swollen bay from the open Venta field: the Fox River Flats shimmered with water where cows graze in summer.

This land was donated by a former Fountaineer to the Kachemak Heritage Land Trust, specifically as bird habitat to be known as the Krishna Venta Conservation Area[4]. Land Trusts must manage their holdings to preserve their conservation values in perpetuity. The risk of liability of a ghost town on such a property is too great: all buildings were razed in 2014. Over there was a workshop, there the washroom, here a cellar perhaps, now a shallow depression cupping an elderberry bush. In the name of forever, an erasure.

This November, we were stuck on the Venta side of Fox Creek: getting back to the road system would have required wading the creek, swollen from a warm spell the week before. We thought the ice was re-forming in the cold nights since, but found the next day that the high tides had raised and ripped out any new ice at the normal crossing. We were the only humans in the valley, excepting a distant neighbor with a bushplane. Because of the warm spells, no hay had yet been hauled out to the cattle; they were fed from hay stored last year, drug in by the trailerload during cold stretches in January and February. Not so long ago, it seemed, there was hay-hauling weather in October and November, but not for many years.

Exoticized perceptions of the environment as wilderness, as frontier, imagine this place as an “outside” and “beyond” to stage imported dramas. I myself was taking advantage of its physical remove to stay apart from the vagaries of the on-road social system: I chose the far side of Fox Creek to weather the pandemic with my partner and infant son. We feel the warm winds which keep us here, think on the dramatic radio news which keeps us here, watch the now-ebbing high waters which erase our trails and keep us here. We wait for change.

Footnotes

[1] pp 281-282. Fisher, John 2008. Spiritual Teachings of Master Krishna Venta. Self-Published. https://www.amazon.com/Spiritual-Teachings-Biography-Master-Krishna/dp/1475285299/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1477688890&sr=8-1&keywords=krishna+venta

[2] pp 33, Fisher 2008

[3] Heupel, Katherine, 2017 “Materiality, Utopia, and Living History at New Buffalo Commune: An Historical Archaeological Narrative of the Sixties Counterculture from Its Unexpected Discards” Columbia University

[4] Kachemak Heritage Land Trust https://www.kachemaklandtrust.org/lands-under-our-care.html