The Poetics of Cloud Seeding: Narratives and Imaginaries of Vapor in the UAE

By Alexandra Cotofana, Assisstant Professor, Zayed University Abu Dhabi

As I am writing this, the plane I boarded in Tallinn took off and is ripping through the clouds. This has always been my least favorite part of a flight, because it causes turbulence. I never quite understood how clouds, these airy nothings, as Richard Hamblyn calls them (2017) can make a giant flying metal bullet shake. I am leaving an environmental anthropology conference in Estonia, and returning to Abu Dhabi, where I teach and where I conduct my research, most recently trying to understand weather scientists and their relationship with clouds. Abu Dhabi is a particularly fertile research site for an ethnography of cloud seeding weather scientists, as the capital of the United Arab Emirates has been experimenting with rain enhancement since the 1990s.

Source: https://i.gifer.com/Ch7.gif

Nestled between saltwater, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Yemen and Oman, the UAE has a subtropical hot desert climate. The country annually experiences two distinct seasons: a hot summer characterized by high air humidity from April to October, and a pleasant winter, similar to the weather you would experience in late spring in the northern hemisphere. Sandstorms are a much more common meteorological phenomenon than light rain, the dessert immensity giving the untrained eye a sense of hopelessness and ruination. Investing in bold technoscience projects like cloud seeding, desert soilification, vertical gardens, and sea water rice plantations allows the Emirates to hope for a successful transition to a sustainable, green future.

Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/Tilal_Liwa_Desert_Reclamation.jpg Author: ClémenceJacqueri

Atmospheric water has long been considered a cheaper alternative to bringing water from elsewhere and a good solution against droughts and floods. Even though the technologies are evolving and diversifying, at its core cloud seeding is a process that mimics nature very faithfully, by scattering ‘seeds’ into the clouds, which results in precipitation (Witt 2016). The UAE is not the first country to experiment with cloud seeding. In fact, news accounts as early as 1893 report engineers in Dublin sending explosives into the sky to increase the water supply in the local reservoirs (n.a. 1893). That day, they achieved a heavy yet short downpour. Similar explorations have been taking place in the US, Australia France, Russia, Greece, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, India, China (Simms 2010). Cloud seeing has not always been led by legitimate institutions: throughout Europe and North America in the 19th and 20th century, charlatans would habitually cheat entire towns out of money, promising them pluvial bliss. Even when the effort to bring rain upon dry lands was honest, it did not always yield the best results. A shift too rapid from innovation to practice left the American public distrustful of cloud seeding in the mid-1900s (Spence 1961). More recently, conspiracy theorists have reinterpreted cloud seeding as an initiative of the deep state, meant to pour toxic salts on the people and the soil of the nation.

The emirate of Abu Dhabi opened the National Center for Meteorology in 2007, and soon after, inaugurated the Rain Enhancement Program (UAEREP), where scientists test scientific hypotheses and launch rain enhancement operations whenever viable clouds are detected. Their visual narratives center the science, technologies, and machines behind successful cloud seeding, revealing where hope is imagined.

The Rain Enhancement Program (UAEREP) is home to a competitive contest that takes place every two years and seeks to fund innovative new technologies for rain enhancement. The call for applications attracts pioneering research projects from around the world and the winner is announced during the International Rain Enhancement Forum, hosted in Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Towers, my first home in the city. Every round, the winner and a couple dozen scientists from the UAE and around the world present the latest breakthroughs in experimenting with cloud seeding. But how did cloud seeding start? And when did clouds become a constitutive element in the cosmology of scientists?

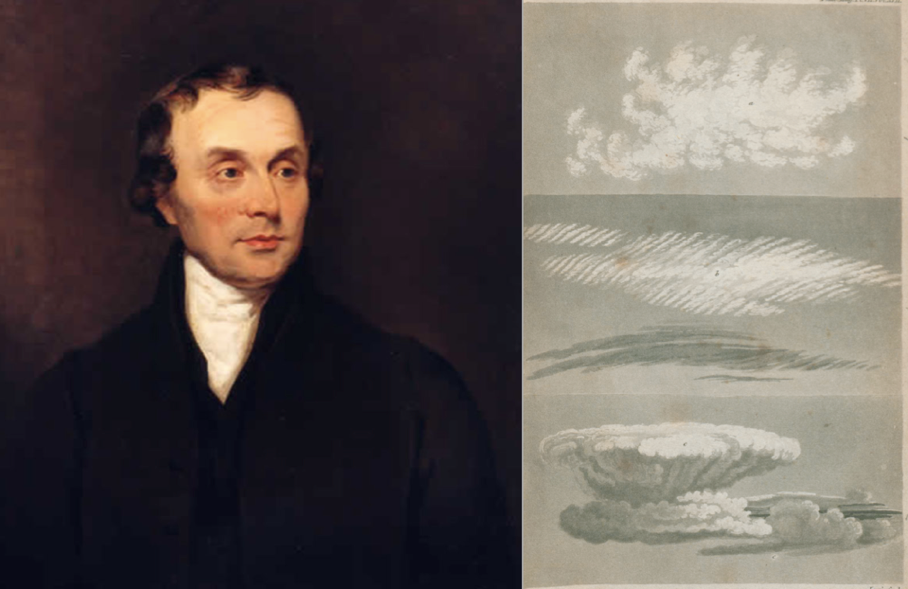

In 1802, then-30-year-old chemist Luke Howard took to the stage in a theater of knowledge in London. Knowledge theaters were hosted by many entities, this particular one was hosted by The Askesian Society, a rhetoric club for scientific thinkers in London (1796-1807), named after the Greek term for “training”. These performances had become an important informal institution during the European Enlightenment, filled with all sorts of inventors, scientists, and their fascinating discoveries. Howard was there to present his most recent discoveries in the modifications of the appearance of water suspended in the atmosphere. At the time, meteorology was treated with increased interest, but people knew too little and paid too little attention to clouds overall. Howard, on the other hand, had observed the clouds enough to give them the taxonomical names we use today (Hamblyn 2001). The next year, based on his presentation at the knowledge theater, Howard published the essay On the Modifications of Clouds, focusing on the principle of their production, suspension, and destruction, which became central to how meteorologists learned to think about the shape and properties of clouds.

A century later, inspired by his childhood summer trips in the Adirondack Mountains, New York chemist and meteorologist Vincent Schaefer started the foundation of what we now call the science of cloud seeding. A mountain-hiking enthusiast, Schaefer started his career at General Electric’s Research Lab in the 1930s, which was then followed by his involvement in several military projects at the start of the Second World War. Schaefer’s interest in the atmosphere was already evident, as amongst his research interests was a project on the creation of artificial fog and one on replicating the patterns of snowflakes. In the mid-1940s, Schaefer moved to the Mount Washington Observatory in New Hampshire and started research on cloud physics. Here he used his breath to create a cloud over a box of dry ice and observed the glittering ice nuclei formed when extreme temperatures met. A couple years later, Schaefer conducted his first successful experiment seeding a natural cloud from a flying plane, which brought him international recognition and publicity. Although for most of his adult life, he collaborated much more closely with academic research institutions such as the American Meteorological Society and Natural Science Foundation, his early involvement with the military allowed for conspiracy theories about cloud seeding to blossom, which still happens today.

The narrative of right-wing platforms such like Breitbart and QAnon condenses a historical populist suspicion of the government and the secrecy surrounding their intentions and projects. From observing unusual cloud pattern to suspecting the covert creation of chemical rain, Breitbart and QAnon supporters across the world do their part in trying to save the planet from geoengineering and weather control.

Often discursively linked to liberal politics, cloud seeding is interpreted by conspiracy theories as a threat. Most recently, American president Joe Biden has been accused of using cloud seeding to flood entire states in the historically republican south of the country, particularly Texas. While some of us might look for explanations on the cause of hurricanes and tornadoes in climate change related science, for right-wing public figures like Alex Jones these are orchestrated by the liberal government to cause harm to the everyday American. Recently, right-wing platform Breitbart has turned its attention to cloud seeding in the UAE, as part of a larger scale narrative that suggests governments have weather weapons.

Meanwhile in the UAE, cloud seeding technologies are developed continuously, in the hopes that a ruined present can somehow turn to a hopeful tomorrow. Ethnographies of science and technology are important, not only because of the historical gap in this type of knowledge production, but also because of the conspiracy theories that have been circulated unbothered in the last few decades. Conspiracy theories offer simple, clear answers, that are presented to individuals under the ruse of exceptional revelation, usually available solely to the alleged global occult elites puppeteering the world from the shadows. Ethnographies that center the voices of the scientists working on cloud seeding have the potential to destabilize some of these beliefs and instead, to offer audiences everywhere a more realistic depiction of what it means to think with clouds.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/UAEREP